Now Playing

Current DJ: Clarence Ewing: The Million Year Trip

Dean & Britta & Sonic Boom If We Make It Through December from A Peace of Us (Carpark) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

If you came of age in a certain time, between the death number one of the vinyl record and the shining pony magic of the digital compact disc, your first album probably came in a 3-by-4 inch plastic cassette. The music clung to a spool in the form of chromium dioxide shavings, and the recording was identified by way of the artist's name in bright red block letters. Once I had saved up eight dollars in allowance so I could buy The Go-Go's Beauty and the Beat from the Nice Price collection, my career as a music consumer was underway.

If you came of age in a certain time, between the death number one of the vinyl record and the shining pony magic of the digital compact disc, your first album probably came in a 3-by-4 inch plastic cassette. The music clung to a spool in the form of chromium dioxide shavings, and the recording was identified by way of the artist's name in bright red block letters. Once I had saved up eight dollars in allowance so I could buy The Go-Go's Beauty and the Beat from the Nice Price collection, my career as a music consumer was underway.

Much later, ten dollars earned from mowing lawns went towards Run-DMC's self-titled album, a purchase that my CHIRP colleague Micha Ward made as well. Both albums influenced my young adulthood greatly. But this isn't about either of those.

This is about the first album I ever stole.

Stealing music in 2014 is a common, impersonal transaction that involves transcontinental cables, satellites, charged molecules and mass digital storage. Actually shoplifting an album today is really awkward. Who does that anymore? The only truly desirable and valuable physical copies of anything are generally pressed to vinyl, and records don't fit in a bulky coat or down the front of your pants. Plus, if you're stealing from one of the few independent record stores left standing, you're a jerk who deserves to be caught.

In the faraway 1980s, things were different. Cassettes available on offer in stores were trapped inside long white plastic discardable ladders, which served to raise the product closer to the customer's eye level. You didn't need a down jacket. You could slide the contraption under your light outerwear, tuck it under your arm, and swing both arms naturally as you exited the store. (The arm swing was very crucial.) Stores started attaching silver magnetic tags that tripped the detectors at the door, but you could peel those off. Stealing music wasn't nearly as easy as it is now, but it wasn't impossible.

Unless, that is, there was a man wearing a badge, with his fingers hooked into his belt loops, waiting for you in the mall concourse. "Come with me, young man," he said. "Don't say a word. We have you on closed-circuit videotape."

The most embarrassing part of being caught stealing a cassette tape wasn't the mark on my juvenile record. The most embarrassing part came three weeks later: the long ride to the courthouse in my father's pickup truck. He didn't say a word to me for the entire ride, just letting the sound of the engine become louder and louder in my head. After I pleaded guilty, he paid the $140 fine for me. On the way back, he finally asked me. "What exactly was it that you stole?"

I didn't have a good answer for him then, and I didn't have a good answer for anyone else. Every time I tell my First Crime story to friends, I leave that part out until the punchline. When I let it slip, the response is usually straight-up bafflement.

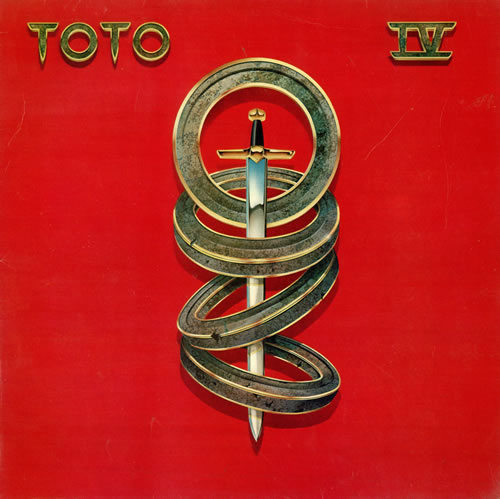

"You stole what?" they'll ask. "Toto IV?"

"Why, Kyle, why? Did you really, really like 'Africa' or something?"

And that's what I would tell them: that I really, really liked "Africa," that million-selling No. 1 smash about Caucasian geographic reductionism. For 30 years, I glossed over the true details, smoothed out the spiky bits, allowed the story to function as a memorable and quirky anecdote that served to illuminate my personality.

Now that I'm thinking about it, though, now that my memory is properly jogged, I remember that her name was Rosalinda. Minor spelling differences didn't matter; it kind of sounded like Rosanna. She was a girl I kind of liked at school, apple-cheeked and olive-eyed with close-cropped brown hair, another monthlong crush that would evaporate in failure before I ever set foot in that courthouse.

But not before I'd spent hours waiting for the Top 40 station to play it. Whenever it did came on, I'd get so excited that I'd shut my door and sing into my sister's hairbrush. (Actually, that was the most embarrassing part.) I'd always be hitting the record button on my boombox a few seconds too late and missing that sweet drum intro, so I needed a full copy, and I couldn't afford one.

My radio hero and friend Jon Solomon, the legendary 24-hour Christmas DJ in New Jersey, was in Chicago a couple months back and he told fellow CHIRPer Mary Nisi and I a funny story over a Pequod's Pizza. He was at a large resort casino in Connecticut, and he came upon a large musical group playing at a sunken stage before a sparse crowd. A cover band, he thought. Then, at the end of the performance: "Ladies and gentlemen, please give a big hand to Toto!"

Toto was formed in 1977 by session players who had worked as backup musicians on records by Steely Dan and Boz Scaggs. The name was chosen because it meant "all-encompassing", which probably didn't seem very ominous at the time. Industry connections secured a contract with Columbia, and extensive promotion led to a long string of Billboard Hot 100 singles, 35 million sales, and six Grammy Awards.

But if you are over 35 years old as of this date, I defy you to remember the name of a single member of Toto. (Without opening Wikipedia in another browser tab.) Other than vague recollections of their voluminous hairstyles, I challenge you to sum up the band's personality in a sentence. If you went ahead and peeked, you now know that there have been no fewer than 25 registered members of the band, a full quarter of the "100 men or more" referenced in "Africa".

We love music because of the personal and emotional connections we have to songs and the human beings who make them. Music bridges singer to audience, DJ to listener, one to another. Music connects friends, lovers, siblings, generations. It's a sacred thing. Mystery and idolatry are essential to the experience: we wonder together what was going through the songwriters' minds at the moment when lyrics and melody were amalgamated. In a universe altogether too lonely, we imagine musicians as kindred spirits. We suppose that our experiences mirror theirs, because we hear an echo of our own souls in the songs.

Bands like Toto were the complete opposite of this. (Who had a Toto poster in their bedroom?) Bands like Toto were empty, faceless, impersonal, corporate canvases upon which to project momentary desires and impulses. Bands like Toto were there to collect your money, vanish in your consciousness soon thereafter, and were destined to reemerge later in New England luxury casinos. And the rock-soul-funk hybrid that Toto helped pioneer would eventually transmogrify into smooth jazz, a fully anonymous, for-profit genre that inexplicably has its own artists, song titles and charts.

If I'd had access to YouTube or a Spotify account in 1982, I'd probably have listened to "Rosanna" ten times in a row and gotten sick of it, and stayed out of legal trouble. But I don't know what would have happened if I'd ended up with a stolen copy of Toto IV, back in an age when an absence of music was still possible, and fostered anticipation. Things might have turned out differently if Toto IV was one of the few albums in my little tape crate; my musical tastes might have developed far differently, and perhaps I wouldn't have ended up at CHIRP. Perhaps I'd have ended up as a keyboard player in a smooth jazz combo instead.

In the end, however, stealing a Toto album and getting away with it would have been the most seriously hardcore punk-ass thing I'd ever done. I do admire the spirit and spunk of that little version of me, whether or not he knew how subversive he was being by trying to take money out of Toto's pockets. But I suffer from the standard regret that all defeated culture warriors feel. And you know what they say about regrets: "there is no second chance for the one who leaves it all behind."

Next entry: Friday iPod/MP3 Shuffle—Happy Birthday Richard Hawley Edition

Previous entry: Weekly Voyages: Friday Jan. 17 to Thursday Jan. 23