Now Playing

Current DJ: CHIRP DJ

Wendy Carlos A clockwork Orange / Theme from Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (Music From The Soundtrack) (Warner Bros) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

[The CHIRP Radio Movie Collection documents great movies that feature musicians or the use of music in storytelling.]

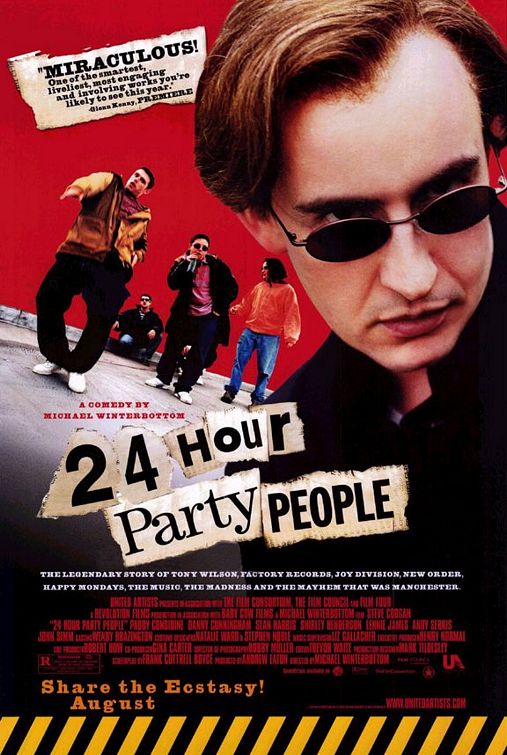

The Plot: The rise and fall of Factory Records, told through the eyes of label founder, Manchester booster, and (depending on who you ask) overall scoundrel Tony Wilson

There’s a story about the history of Rock music that’s almost certainly apocryphal but is too good to not use: Only a couple of hundred people ever saw the Velvet Underground perform live, but every single one of them went on to form their own bands. This brief anecdote highlights the power music has over people, a power that remains explainable more by magic than science.

It’s this magic of discovery and creation and being part of a scene that’s captured brilliantly in 24 Hour Party People, the story of how local TV presenter Tony Wilson helped briefly turn the city of Manchester into the center of the music world with his label Factory Records. Director Michael Winterbottom starts the film with a VU-eque sequence - in this case, a late ‘70s Sex Pistols show with about a dozen people in the audience. Wilson, the narrator, scans the room and points out a few of the not-yet-known individuals in attendance: The young woman over there with the wild hair would soon be known as Siouxie Sioux of Siouxie and the Banshees. The curly-haired dude off to the side would become the lead singer for Simply Red. And the three intense-looking young men in the back? They would start a band called Joy Division, and in doing so change the course of music history.

From there, Wilson (perfectly played by Steve Coogan) is the audience’s guide in the creation of Factory Records and what would become known as the “Madchester” scene. The label’s ascendance is personified by Joy Division and its charismatic and doomed lead singer Ian Curtis. The movie depicts the creation of the band’s first records using the brilliantly abrasive Martin Hannett as producer, a process that included putting drummer Stephen Morris on the roof of the recording studio to get the exact percussion sound needed. For those interested in seeing depictions of the creative process, these scenes are thrilling.

Curtis’ death by suicide functions as the turning point of the movie, even as the surviving band members reorganized to make history as New Order. Factory’s functional demise is lead by the band Happy Mondays, a volatile alternative dance group led by brothers Shaun and Paul Ryder that indulged in all the sex and drugs Rock and Roll had to offer. Their story includes an ill-advised trip to the Caribbean and the use of gunplay to settle the ownership of vocal tracks for their new album.

Along the way, the audience is given a tutorial in the ups and downs of running an independent record label by someone whose love of his hometown is perhaps matched by his incompetence as a businessman. The label’s world-famous club The Hacienda would soon become unworkable due to a healthy contingent of drug dealers and patrons who would rather spend their money on pills and pot than alcohol. “Never lose control of the door” is one of the hard-won insights gained from Wilson’s experiences. Another one is that if a band is on your label, it’s probably a good idea to get contracts signed in something other than blood.

24HPP isn’t a documentary in the correct definition of a collection of meticulously researched facts, verified timelines, and certified quotations. It may be, though, one of the most honest histories of music ever made, as it is told from the biased perspective of a person. In telling the story, Wilson exaggerates, he makes things up, he leaves things out, and he always positions himself as the champion of culture and community he thinks he is. In other words, he remembers things the way everyone remembers things; His versions of events are his own and are different from those of the friends and enemies he makes along the way.

Winterbottom seems to use every cinematic gimmick to tell the story, and it all works. Wilson breaks the fourth wall to speak directly to the audience. Timelines are presented out of order. Scenes are enhanced with cheesy, low-tech effects. The actual people events are based on (including the real Tony Wilson) make cameos as themselves or other people. Sequences switch from straight narration to fictional reenactment and back again. The cinematic tricks that might quickly become cliche in another film make this one stronger by reinforcing its fantastical, hallucinogenic qualities.

Despite the historical inaccuracies, or maybe even because of them, the movie captures the spirit of a time and place in a way that might not have been possible in a by-the-numbers traditional doc. It’s not merely a recitation of events - it’s describing the birth of an idea, a movement. And it’s one of those retellings that might make the audience want to be there.

Next entry: The Blake Babies Reunion Show is at Evanston SPACE This Saturday!

Previous entry: Top Five Songs the Republicans Could Use for Their Convention